In The Flow of Time – August 10, 2024

I thought I’d try to convey the random (?) fun of burrowing down rabbit holes. I’m not taking notes about how I do it when I’m doing it. So this story is really a “like this” exposition, not a precise accounting of a typical morning in the life of the historical fiction researcher. (Really, I’m avoiding the “work” part of what comes next. This is more fun.)

I’m reading about Marie Laveaux’s Voudou practice. Weeks ago I decided to spell it that way because Voudou is a Louisiana Creole word (a proper noun) that (hopefully) will cause you to think twice before equating a genuine African religious tradition with occult hokum.

In truth, we know almost nothing about what Marie Laveaux did as a Voudou priestess. She didn’t write anything down, she was illiterate. What we have is oral history captured 60-80 years after the fact; and breathless newspaper reporting about satanic orgies written through the very distorted lens of white Christian supremacy. We have uninitiated men and women observing and describing that which they do not understand. So, if I can separate judgmental crap from descriptions of a parterre altar, I can start grabbing a clue.

Reading along, I encounter Charles Raphael, born in 1868, interviewed in the 1930s by the Louisiana Writers Project. He describes the altar in Marie Laveaux’s front room. “She had a statue of St. Peter and St. Marron, a colored saint.” Other reading educates me on the amalgam (syncretization) of St. Peter with Papa Labas, the Voudou equivalent, the keeper of the gate. But who is this Marron guy?

Down the rabbit hole I go.

A “maroon” in this context is a runaway slave. “Marron” is the French spelling. Writer thought: I’ll use “marron” to avoid the looney-tunes “what a maroon.” This is a case where using a foreign word works better. I’ll define it in the story when it shows up. The etymology is Spanish. Runaway slaves hiding in the swamps were simarrónes, “wild” or “untamed.” The word applied equally to livestock or slaves.

Marron escapees had entire communities in the cypress swamps around New Orleans. They moved in and out of the city, selling firewood or garden vegetables. But they were runaways and subject to recapture.

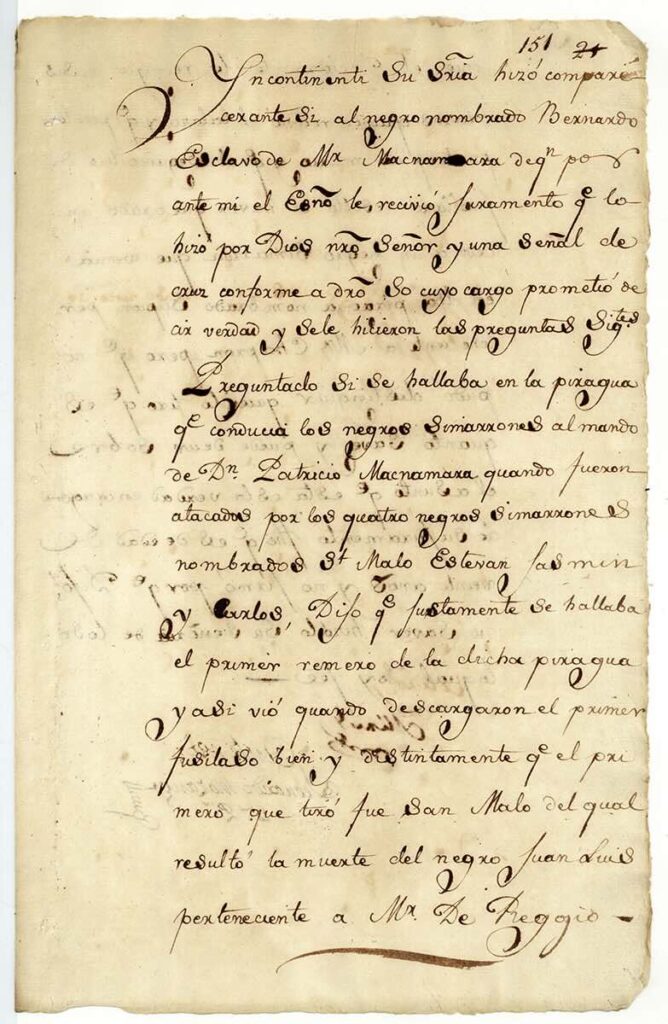

Deeper down the rabbit hole I come across an historical figure, Jean Saint Malo, circa 1780. Back when Spain ran things, he escaped and led a community near Lake Borgne. They had weapons provided by friends among the free colored people of New Orleans, or stolen from plantations. According to legend, San Maló buried his hatchet in the first cypress knee of Gaillard Island, saying, “Malheur au blanc qui passera ces bornes,” meaning “Woe to the white man who would pass these borders.”

He escaped from the d’Arensbourg plantation. We know that his wife’s name was Cecilia. We know she was pregnant at the time of his death. For the legends around him, you can think of a bit of overlap with Robin Hood (for western white folk). He was an outlaw, fighting for the poor and repressed, stealing a living from the city.

Jean St. Malo was captured by the Spanish in 1783, condemned to death by hanging, and was executed on June 19, 1784. They didn’t remove the body, they let it hang and rot from the gallows in what is today Jackson Square in the heart of the Vieux Carré of New Orleans. Legend says that as he rotted, the Voudou practitioners took bits and pieces for the powerful magick associated with Jean St. Malo.

If you find this repulsive, think of the Catholic practice of using and enshrining the leftover bits of saints, holy relics. It is precisely the same thing. The overlap between the “superstitions” of African religious belief and the “superstitions” of Catholic religious belief is where New Orleans Voudou comes from. The Catholic religion is mandated, all slaves must be baptized and taught the true faith. They were, and easily related the story of the Virgin to Mami Wata, and St. Peter to Papa Labas. They might as well be the same thing. The local Black people wrapped their true religion inside the blanket of Catholicism.

Jean St. Malo is part of that. He was such a legendary figure that the oppressed people of New Orleans made him a de facto saint, the patron saint of runaway slaves. Think “St. George the Dragon Slayer.” There is no Saint George in the Catholic pantheon. There is a Saint Maron, a 4th-century monk in what is now Syria whose followers became the Maronites. Not the same guy. 🙂

Jean St. Malo lived before the time of my story. I’m going to start around 1812. But stories, and lives, do not happen in isolation. Jean St. Malo is part of the local history, and St. Marron is the local legend, the ground on which Marie Laveaux walks. If Jean St. Malo were a central part of my narrative, I’d want to go much deeper. For how the story is coming together in my head, this will suffice.

Back in the 1930s, the Louisiana Writers Project interviewed Charles Raphael. Sixty years after the fact he remembers something he saw when he was maybe ten years old. “She had a statue of St. Marron, a colored saint that white people don’t know nothing about.”

Deep down the rabbit hole I go because I thought it would be interesting. It is, and in some small way it is very likely to make it into my story.

Learn more about Jean St. Malo here: https://www.noirnnola.com/post/2018/07/30/jean-saint-malo-the-man-the-maroon-the-martyr