In The Flow of Time – May 10, 2025

The Catholic church picked a new Pope the other day. It turns out, he has roots in Creole New Orleans. Friends who know what I’m writing immediately asked if I’d seen this news. Yes indeed. I’m writing 50-100 years before his grandparents got married in New Orleans. His great grandmother was baptized in the St. Louis cathedral in 1840. And there we are back in the time of my novel, which will run from 1811 to 1860.

The modern event brings up a host of truths. Not the least of which is the word “Creole.” Racists insist that only a white person can be Creole, because it means “born in Louisiana” and people of color don’t count. They believe that the use of “Creole” to mean a melange of colors, cultures, and cuisines is a corruption that mirrors the social corruption of race mixing.

Fuck ‘em.

At the turn of the century, 1800 that is, New Orleans was an astonishingly vibrant little city. It had yet to grow, but the sprouts were already there, of both greatness and misery.

Roughly speaking, the city was one third white (French and Spanish), one third Black slaves, and one third free people of color, many of them of mixed race. That’s an oversimplification. There were people from many African nations; European nations; Canada; Mexico; the Caribbean islands, even the United States. There were many languages: Kikongo; Yoruba; Wolof, Choctaw, Spanish; French; English; a bit of German and Italian. Government had gone from French to Spanish and back to French. The Americans were about to show up. Native Americans were already a remnant.

People of all races mixed, more or less freely. Some free people of color achieved social and economic status equal to or greater than people of purely European heritage. A slave could purchase their own freedom. Black shopkeepers had white customers, and vice versa. Legal segregation did not exist.

Culturally it was libertine, wild, unruly. Antebellum New Orleans was the Las Vegas of its time. There were girls, pool halls, gambling, horse races, lotteries, interracial dances. Poker was invented here, and probably backgammon, out of older forms of the games. A new language appeared, Kouri-Vini, used among the masses.

Slaves had Sunday off! They partied in what today we call Congo Square, a wild melange of music and dance rooted in a dozen African nations and languages. New music and dance appeared as disparate traditions and instruments wove into new patterns.

New Orleans was unique in the world, a cosmopolitan center unlike anywhere else.

Yet the seeds of oppression were already there. Slavery was rampant, and keeping slaves “in their place” was a real issue. It got worse with the arrival of puritanical Americans, deeply offended by the idea of having fun. In the decades before the American Civil War the noose tightened. Free people of color never had the right to hold public office, and it went downhill. It became harder to free a slave, until it was impossible. It always mattered what your skin color was, but it mattered more. And more. Any religious service had to be led by a white man. Segregation appeared. Pillories were OK for Black people, but not for whites. Free people of color were not invited to the reunion of those who fought in the Battle of New Orleans. In the end, every free person of color was ordered by law to choose the white person to whom they would be enslaved. We live with the fruit of that oppression to this day, two centuries later.

Marie Laveaux, the Widow Paris, is quintessentially New Orleans: Wolof, Kongo via Cuba, French Canadian, Native American. She is a priestess of the old religion as it has transmuted in the new world. She is also a devout Catholic. She is a hairdresser, a healer, and a priestess. She is a free woman of color, and she owned slaves. She accomplished great things, within tightening limits. When the racist white men appeared begging for her help in an epidemic, she helped. It’s who she was.

The descent of New Orleans into racist hatred is the canvas upon which she lived her life. I don’t know yet how I’m going to convey that. But I have one story that I think reveals in contrast the truth of life in New Orleans about 1830. And that brings us back to the Pope’s ancestors.

The 1900 census identified them as Black. In 1910, the same people are white. Because life had become binary. All the thousands upon thousands of people with a multi-faceted heritage were far better off if they could pretend to be white. This was always true, but became much more so during Marie Laveaux’s lifetime. Many pretended to be white. Even in the 1830s. And now, the contrast.

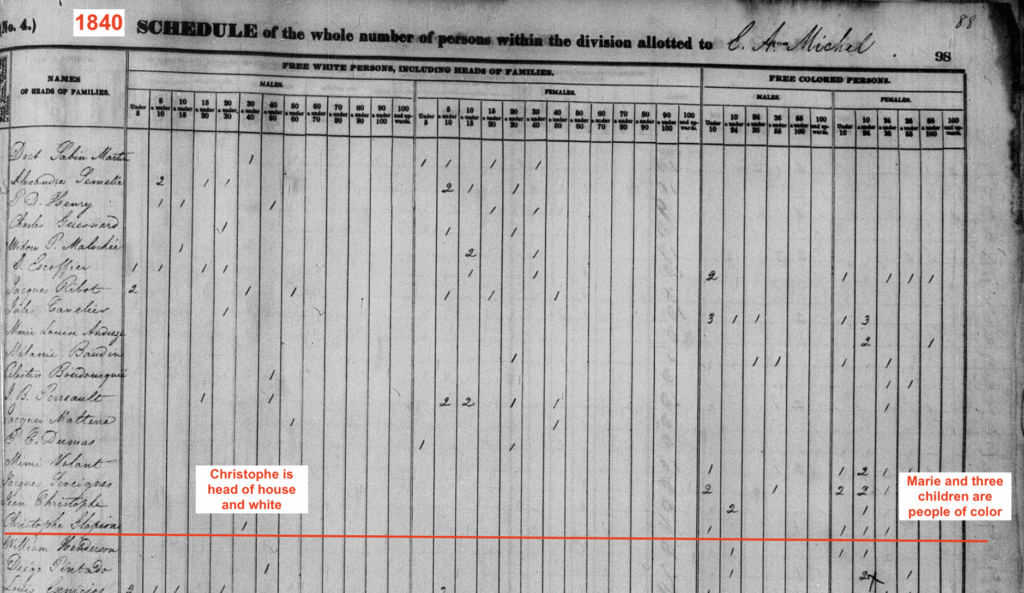

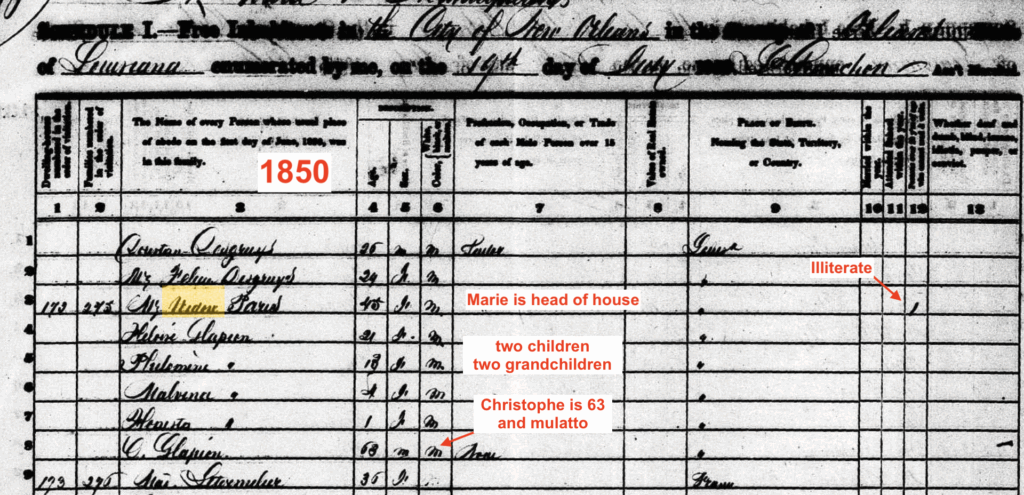

A white man from France, Christophe Glapion, fell in love with Marie Laveaux. She accepted him and he lived with her for the rest of his life. They never married, because that was illegal. It was illegal for them to even live together. Yet they did, for decades. How did a white man and a free woman of color get around the law?

Where many strived to pass for white, Christophe Glapion passed for Black to live with the woman of his dreams. I suspect he was white when it suited, and Black the rest of the time. He lived with a foot in both worlds. Like the Pope’s ancestors, he shows up in one census as colored, and in another as white. Truth, I suspect that being able to pass in both worlds meant that he could escape SOME of the social cost. But it wasn’t zero. I have the documents, the real estate transactions, the wills that show the family finagling the oppressive system to maintain a legacy.

I don’t know, yet, how I’m going to paint that darkening canvas of rising hate against which Marie and Christophe lived their lives and raised their children. The legacy of the free people of color, and the cosmopolitan mix that was New Orleans, gave us jazz, blues, tap, and a joie de vivre that belies the oppression that bound their lives. They could not escape the bounds, but they refused to be crushed.

I find that AWESOME, and a tale worthy of telling.