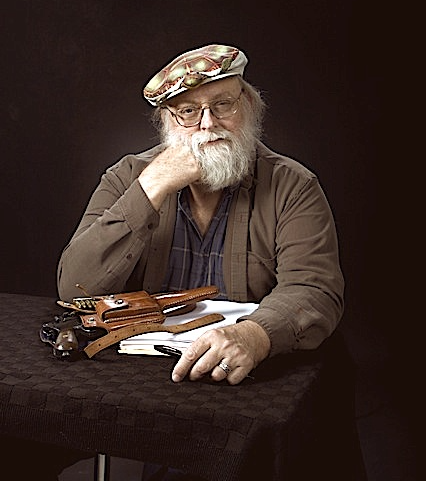

Bio

Having been born in the late 1940s, I grew up with stories (thanks to my Dad’s tastes) from the late 19th and early 20th century, particularly the works of H. Rider Haggard, Zane Grey, and Edgar Rice Burroughs. It wasn’t until my early teens that Dad dropped a copy of Heinlein’s Puppet Masters on my bed, saying ‘Here, this will keep you up all night.” It did, and I became an instant science fiction fan, devouring Heinlein, Bester, Asimov, Simak, Sheckley, Poul Anderson, Le Guin, and all the rest of those pioneers of SciFi.

My love affair with High Fantasy didn’t really bloom until I discovered J R R Tolkien in college. Such passion!. I have never looked back. My first efforts at writing my own stuff grew out of a shared interest (with my wife) in high fantasy. So my first 4 novels were pretty much sword and sorcery tales. Eventually I got to the end of my sword/sorcery stories and found a new passion in the Aero Rangers tales, set in the 1920s and 30s.

Characters in my Aero Rangers stories are heros of another age. The adventures I preferred, by Authors like Edgar Rice Burroughs, Zane Grey and H. Rider-Haggard featured clean cut heroes who never cursed, never had sex, and only villains drank alcohol.

Characters in mainstream adventure stories reflected the expectations of polite, middle-class western society. Lantern-jawed, two fisted heroes were Expected to be clean-living, polite, and never use bad words in the presence of a lady. Ladies weren’t supposed to know those words. But of course we know it wasn’t so, or those Other words would have disappeared out of the language.

Surviving accounts of soldiers from the Great War tell another tale. Men who underwent the Hell of day-long bombardment by heavy artillery, or saw their companions gassed or roasted alive by flame throwers learned another way of speaking. The expectations of polite civilization died in the trenches. But when they came home, the old rules were expected to apply.

My heroes occupy a strange place somewhere between peace and war. Legally the Aero Rangers are an international police force, and expected to be exemplars of the League’s civilizing influence. In practice, their vocabulary is a compromise between war and peace, but generally they watch their mouths.

When certain words and phrases can only be used in the toilet or on the battlefield, people are forced to adopt euphemisms. So we get a wonderful selection of words of opprobrium. A rotten Sonovabitch or Asshole becomes a bounder, cad, louse, scoundrel, villain, cutthroat, goon or thug.

In the presence of ladies one simply couldn’t shout ‘Holy Shit” no matter how grim the occasion. You could say: Jumping Jehosophat, 23 Skidoo, Zounds, Holy-Moley, or Whiz-Bang.

Part of the fun creating adventure yarns is in mining the language for appropriate phrases. Can our heroine say ‘that guy gives me the creeps?’ Not before @ 1950. But she can say ‘he gives me the Willies’ which means the same thing. I wanted to give one of my heroines sneakers. Could I justify that in 1931? No problemo: rubber soled ‘gum shoes’ date back as far as the 1880s. A gumshoe could be either a sneak thief or a detective who catches them.

For aerial combat, there’s a whole vocabulary of specialized terms (the same goes for sword-fights, hand-to-hand combat, etc.) Airmen in the Great War referred to their machines as ‘kites’, gasoline or petrol was ‘juice’. To crash on landing was to pancake, ‘prang’ or ‘crack up’, Fighter planes were scouts, and later pursuits. A two-seater has a ‘front office’ and a ‘rear office’. Various maneuvers have wonderfully evocative names, like split-ess, Immelman, chandelle, and wing-over.

As tempting as these specialist terms are, I prefer to use them sparingly. Given that the average reader may not know any of the terms, I use them deliberately, when the occasion demands. The purpose of describing aerial combat isn’t to prove your author knows all the terms, but to describe a twisting, turning, desperate combat by frightened pilots flying fragile machines made of sticks and canvas. Story telling comes first. Education in specialist terms is secondary.

A combat pilot’s life was far from easy. It’s cold at altitude, fliers got ear infections from constant changes in air pressure, A lack of oxygen produced pounding headaches, while judgement faded into fuzzy thinking. Before the invention of adequate instruments, disorientation when flying at night or in cloudy conditions could end with an unexpected meeting with the ground.

Before the advent of modern communications, talk between aircrew was either by voice-tube or hand signals. Talk between aircraft was effected by flare-gun or wing waggling at longer distances, and hand-signs if nearby.

For purposes of narrative convenience, I gave my flight-leaders voice-radio for Aeros III (1927) That’s a bit early, but the Aeros Do have an top quality gadgeteer in Edmund Tailor. He ought to be good for something.

Up to @ 1940, standard weapons for scouts/pursuits/fighters was a pair of .30 cal machineguns up front, with 300-500 rounds per gun. Figure on no more than One Minute of shooting-time. Two seaters often provided a single .30 cal. machinegun in the back seat. A few airforces (the French for instance) began to outfit their interceptor fighters, with 20 mm auto-cannon for dealing with the new heavy bombers.

In WWI, the Royal Airforce developed dive-bombing (approach at Very Steep angles) with SE5a pursuits. After the war, the US Army Aircorps put plenty of work into dive bombing. The RAF lost interest in the tactic by WWII, but on seeing demonstrations by US Curtiss dive-bombers, the Luftwaffe went whole-hog into steep diving attacks for pinpoint accuracy.

Novels

- 1920: Tunguksa Terror (Aero Rangers vol. 1)

- 1923: Army of the Dead (Aero Rangers vol. 2) Forthcoming

Heroes of the Age

Some of my fondest memories from childhood are of my father reading aloud from Burroughs’ Tarzan stories. When we got old enough to read for ourselves, Dad would halt the story at some exciting point and leave us to carry on. I spent much of my youth reading. After devouring most of Edgar Rice Burroughs and Zane Grey, I moved on to H. Rider Haggard, and eventually branched out into science-fiction: Theodore Sturgeon, Robert Sheckley, Arthur Clark, and Robert Heinlein.

I attended public schools in Orange Texas, followed by four years at Lamar University in in beautiful Beaumont Texas. In 1970, I moved on to the Promised Land: University of Texas at Austin, where I earned a Master’s degree in battleships. I know more than you could ever want to about dreadnought battleships and the Anglo-German naval rivalry of 1900-1918. Fifty years later, I’m still in Austin Texas, surrounded by a huge collection of volumes on battleships, aeroplanes and medieval weapons.

In graduate school I discovered the works of JRR Tolkien. Wife Kathleen and I took turns reading aloud from Lord of the Rings, every Monday evening, starting on Bilbo’s day.

After Kathleen passed away in late 2000, I started writing my own stories. Now, I have four sword and sorcery fantasies in manuscript, as well as five Aero Rangers adventures, with two in work. After that, who knows? I’ll think of something.

It’s difficult to produce quality work in a vacuum. I have been encouraged by friends who sat through endless readings, kindly offering suggestions. If I have succeeded, it’s due in part to the support of the Monday night reading-aloud gang, who were there when I needed them most.